In recent months, my wife and I have been catching up on the Daniel Craig trilogy of 007 movies, and I’ve been watching Batman cartoons with my seven-year-old son. So my thoughts have been full of action heroes — particularly the Dark Knight and Her Majesty’s secret servant.

In recent months, my wife and I have been catching up on the Daniel Craig trilogy of 007 movies, and I’ve been watching Batman cartoons with my seven-year-old son. So my thoughts have been full of action heroes — particularly the Dark Knight and Her Majesty’s secret servant.

I remember my father complaining about both characters and contrasting them to the lone-hero tradition of hardboiled detectives and their fictional forebears, the cowboys.

G.I. vs Private Eye

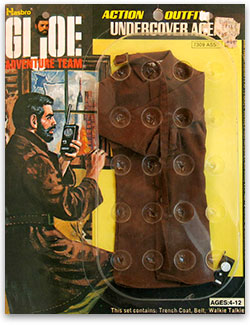

In fact, my father’s point to my preteen self was a continuation of a point he made to me when I was about my son’s age. I’d just gotten a set of “Undercover Agent” accessories for my GI Joe doll (we didn’t call them action figures back then). Gone were the camouflage fatigues and assault rifle; now Joe sported a dark trench coat and a walkie-talkie.

I said, “Look dad: It’s GI Private Eye!”

I said, “Look dad: It’s GI Private Eye!”

My father explained to me that my rhyming name for my new hero was self-contradictory. A GI was an American soldier, an official agent of the US government, whereas a “private eye” was a private individual, a lone hero in the fictional tradition. If dad had been more of a libertarian, he would have said that the military agent is paid by coercively extracted taxes and operates by state privilege, whereas the private detective is an agent of the market, authorized only by private contracts, and liable to the same restrictions as any individual citizen. My father doesn’t talk that way, even now, but he would acknowledge that description as making the same point.

So after GI Private Eye, I grew up with an awareness of the distinction between heroes like James Bond, who was funded and sanctioned by the government, and heroes like Philip Marlowe, who was funded by private clients and sanctioned only by his personal code of conduct.

Astin-Martin vs the Batmobile

Now, a few years later, my father was making a different but related point about James Bond, this time inspired by my love of another toy: my Corgi Astin-Martin DB5, James Bond’s super spy car from the movie Goldfinger. “Look dad, isn’t this car cool?”

Ever philosophical, my father saw the car as symbolic, not only of that state-agent/private-individual divide he’d addressed a few years earlier with my GI Joe, but also of a divide in heroic literature. James Bond worked for the queen, he explained, in Her Majesty’s Secret Service. He was a knight for the monarch, and this tricked out vehicle from MI6’s Q Branch was the 1960s adventure-fantasy equivalent of the nobleman’s armor and mount.

Ever philosophical, my father saw the car as symbolic, not only of that state-agent/private-individual divide he’d addressed a few years earlier with my GI Joe, but also of a divide in heroic literature. James Bond worked for the queen, he explained, in Her Majesty’s Secret Service. He was a knight for the monarch, and this tricked out vehicle from MI6’s Q Branch was the 1960s adventure-fantasy equivalent of the nobleman’s armor and mount.

I believe he felt the same about the Batmobile, but there are several important distinctions, some that put the historical emphasis on the “knight” in the Dark Knight, and some that put the “World’s Greatest Detective” more in league with the private eyes of American detective fiction.

For one thing, the medieval knight was a soldier for the king because he could afford to pay for armor, weapons, and a battle horse. He could afford to head off into battle instead of plowing the fields — and he could afford the time required for training between wars. The king didn’t pay him to be a knight. He paid the king for that honor. As far as we can tell, James Bond isn’t paying out of pocket for all those vodka martinis, and he certainly didn’t commission Q Branch for any of his gadgets. 007’s license to kill makes him a hired gun, even if he does restrict his paid murders to those sanctioned by his government.

Batman, on the other hand, pays his own way.

The Dark Knight of Liberty

Like most of the medieval knights, his wealth originally came from privilege more than trade. The Waynes are old money. Even “stately Wayne Manor” suggests aristocracy, and where Superman’s Metropolis is shiningly new and forward looking, gothic Gotham is old, with deep roots in Europe. Frames of Batman on the rooftops harken back to Quasimodo atop Notre Dame.

But while WayneCorp may well have risen on government contracts, Batman is not on the payroll. Bruce Wayne is spending his own money to fund his war on crime. This may put him in the ranks of the feudal warriors, but it sets him apart from agent 007.

Finally, who are the bad guys?

For Bond, they are the enemies of the state — meaning that they are whoever Her Majesty says they are. In both the books and films, they are invariably evil, so James Bond will look like the good guy when he finally defeats them, but ultimately the double-O agents are weapons: the government aims them at its enemies and pulls the trigger. We know full well from history who ends up in the crosshairs.

Even my favorite fictional private eyes, however independent and heroic they may prove to be, don’t go looking for trouble until a client hires them to do so.

But for Batman, the enemy is crime — not mere violators of legislation and statute law, not people who manufacture without regulation, trade without license, or copy digital patterns in violation of copyright. A true comic-book fanboy could probably dig through back issues and show us the exception, but I can’t recall Batman ever even picking on drug users.

For Batman, as for libertarians, a crime isn’t a crime without a victim. And it is the victims Batman is fighting for; they are proxies for the parents he was too young and scared to rescue from the back-alley gunman. In the versions of the backstory that I prefer, Batman can never avenge his parents’ deaths, so even the target of his vengeance is a proxy: not a human criminal but crime itself. And by “crime,” I mean rights violations, violence against person and property.

The Dark Knight may be on a perpetual quest, but it is not for a king; it is for the people.