Murray Rothbard, the great libertarian theorist and economist, hated Goodfellas. He especially hated the depiction of gangsters as “psychotic punks” whose violence was “random, gratuitous, pointless.”

Murray Rothbard, the great libertarian theorist and economist, hated Goodfellas. He especially hated the depiction of gangsters as “psychotic punks” whose violence was “random, gratuitous, pointless.”

He preferred the Godfather films, where the gangsters never engaged in violence “for the Hell of it, or for random kicks,” but only used it to enforce contracts the government police and courts wouldn’t uphold.

For Rothbard, Goodfellas’ unflattering portrait of gangsters was practically a smear on libertarianism itself. According to him, “[o]rganized crime is essentially anarcho-capitalist, a productive industry struggling to govern itself,” which provides consumers with products — such as gambling, drugs, prostitution, imports — that the government has arbitrarily and unjustly made illegal. So he was offended by Goodfellas, where the “organized” criminals are little different from “street” criminals and are defeated by the cops in the end.

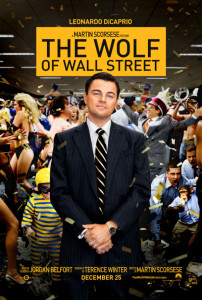

Some libertarians may dislike Goodfellas director Martin Scorsese’s latest, The Wolf of Wall Street, for similar reasons.

This film tells the story of a stockbroker, Jordan Belfort (Leonard DiCaprio), who cares about nothing but money and gratifying himself. His startup Long Island brokerage takes off when he and his cohorts start pushing penny stocks on working-class investors by cold-calling them and convincing them they can get rich quick by investing in purportedly great companies that are actually terrible. Belfort makes even more money by using third parties to invest in some of the companies whose stock he pushes and stashes the profits in a Swiss bank account.

Meanwhile, Belfort and his colleagues’ lust for money leads quickly to Caligula-style decadence, with non-stop sex-and-drug parties in and out of the office, which the movie dwells on at length.

Just as Goodfellas never acknowledged the valuable services Rothbard believed the Mafia historically performed, The Wolf of Wall Street never acknowledges the essential service that stockbrokers provide in a market economy. A character played by Matthew McConaughey — who, like Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross, appears just once early on to deliver a memorable greed-stoking speech — claims that stockbrokers don’t “create” anything but just pointlessly move money around while taking a cut for themselves.

At that point, some libertarians may be tempted to walk out, assuming that the rest of the movie will be an attack on capitalism. But walking out for that reason would be a mistake, and criticizing the movie for that character’s statements would be misguided, just as Rothbard’s criticism of Goodfellas was misguided.

Rothbard failed to mention that Goodfellas, unlike The Godfather, was a true story. Those characters did those things, more or less. In fact, the Mafia does not just engage in Defending the Undefendable-style heroism by providing black-market goods and services; it also engages in theft, insurance fraud, protection rackets, vending machine rackets, and other thuggery. And who carries out these activities? Thugs, of course: mediocrities who see gangsterism as their chance to become a “big shot,” like Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill, and psychos who see an outlet for their violent inclinations, like Joe Pesci’s Tommy DeVito. (Come to think of it, if we want to use the movie to make a libertarian point, we might observe that government attracts similar lowlifes for the same reasons.)

Whether you want to see a movie showing the real-life violence those people carry out is up to you. Randians, I assume, would argue that art shouldn’t depict anything so ugly and but should instead show us man at his best — so they wouldn’t want to see it. But I find it interesting to get a glimpse of how such people think and live — and Scorsese could not have done a better job telling their story. So I have no complaints about Goodfellas.

The Wolf of Wall Street is not a masterpiece like Goodfellas, but I approve of it for similar reasons. It too is based on a more-or-less true story. We can’t know whether Belfort fabricated or exaggerated details in the memoirs on which it’s based — if the office orgies shown actually happened, one would think hostile-work-environment lawsuits would have shut the place down long before the SEC or FBI noticed it — but the parts about Belfort’s stock trading are basically correct, as far as I know.

And I don’t doubt that some stockbrokers are jerks whose views aren’t much different than those of the McConaughey character. After all, most of them aren’t economists, so why would they understand the important role they play or how the economy works beyond what’s necessary for them to do their sales jobs? And there have, in fact, been “boiler rooms” where salesmen push bad stocks on ignorant people. Libertarians are not obliged to approve of such things or pretend they don’t exist, though we can point out that they are the exception and not likely to last long in a true market economy.

So what’s wrong with making a movie about those people? Nothing, as long as it holds the viewer’s interest and doesn’t try to make a broader point about all stock trading being evil.

The Wolf of Wall Street passes that test. There are vague allusions to “the one percent” and Wall Street’s role in our recent economic troubles, but there is no “message” apart from the obvious one that greed can lead people to be short-sighted and nasty. So I don’t think the film is especially objectionable from a libertarian perspective.

From an artistic perspective, there’s room for debate. You get the sense that the movie aspires to be Goodfellas set in the financial world, but it falls short. Like Goodfellas, it opens with a preview of an especially over-the-top scene from later in the film. It also uses a freeze-frame effect familiar to anyone who has seen Goodfellas, and it has similar narration by the main character. You can tell Scorsese is trying to recreate that movie’s visceral effect, but he doesn’t quite succeed.

And although the broad strokes of the story may be true, many details feel false. The characters go from ordinary to outrageous too quickly, and the office parties seem implausible in the 80s and 90s, after the rise of sexual-harassment lawsuits and political correctness. And while Goodfellas showed an Italian-American subculture that Scorsese had observed first-hand, Wolf creates a world whose look and feel he can only guess at — and you can tell.

Also, he reportedly kept editing this movie — to three hours, down from four — until the last minute, and it feels like he still didn’t get it quite right. You get the sense there is a tighter, better movie that could have been made of it.

Still, if you’re not offended by films that dwell on vice, crime, and the people who engage in them, it’s worth seeing. DiCaprio is great as always, and Jonah Hill is pretty good as his sleazy partner. Despite the excesses, I appreciated the depiction of how people can behave — against their own long-run interests — when they believe they’ve discovered a way to wealth and happiness that does not require them to think about how they can actually benefit their fellow man.