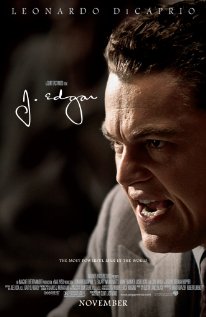

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

The current generation might imagine that the egregious overreaching of the state in the name of security is something new, perhaps beginning after 9/11. The film shows that the roots stretch back to 1919, with Hoover’s position at the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation under attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer. Here we see the onset of the preconditions that made possible the American leviathan.

Palmer had been personally targeted in a series of bomb attacks launched by communist-anarchists who were pursuing vendettas for the government’s treatment of political dissidents during the first world war. These bombings unleashed the first great “red scare” in American history and furnished the pretext for a gigantic increase in federal power in the name of providing security. In a nationwide sweep, more than 60,000 people were targeted, 10,000 arrested, 3,500 were detained, and 556 people were deported. The Washington Post editorial page approved: “There is no time to waste on hairsplitting over infringement of liberties.”

Here we have the model for how the government grows. The government stirs up some extremists, who then respond, thereby providing the excuse the government needs for more gaining more power over everyone’s lives. The people in power use the language of security but what’s really going on here is all about the power, prestige, and ultimate safety of the governing elite, who rightly assume that they are ones in the cross hairs. Meanwhile, in the culture of fear that grips the country – fear of both public and private violence – official organs of opinion feel compelled to go along, while most everyone else remains quiet and lets it all happen.

The remarkable thing about the life of Hoover is his longevity in power at every step of the way. With every new frenzy, every shift in the political wind, every new high profile case, he was able to use the events of the day to successfully argue for eliminating the traditional limits on federal police power. One by one the limitations fell, allowing him to build his empire of spying, intimidation, and violence, regardless of who happened to be the president at the time.

There is a startling scene from 1932 surrounding what H.L. Mencken called the “biggest story since the resurrection”: the kidnapping of the child of Charles Lindbergh. When the federal agents showed up at Lindbergh’s house, they are treated as interlopers without any authority over the matter. The New Jersey police had the relevant jurisdiction here. Hoover fumed about this event and used it as the pretext to demand wider authority. The eventual result was to make kidnapping a federal crime, thereby setting a precedent for the eventual federalization of any and all crime. Today there is essentially nothing outside the jurisdiction of the feds.

(As a side note, making a brief appearance in the film is the role of FDR’s gold confiscation in the course of the investigation. The ransom was paid in gold certificates, which FDR had ordered be surrendered by federal criminal law by May 1933. The spending of these notes after this date is what tipped off merchants about possible criminal activity.)

World War II furnished more fodder for Hoover’s march toward total power. The Cold War was next. The civil rights movement and antiwar movements were next. At each stage, Hoover was able to regain his reappointment through a subtle blackmailing of each new president and whipping up of public hysteria based on the latest headlines about criminal activity and the need for federal intervention and control.

Was Hoover popular in the public mind? According to the movie, his popularity ebbed and flowed but mostly ebbed. This bothered him but it hardly mattered. He and his policies were never subjected to a plebiscite though he exercised incredible power as the head of an agency that had more in common with the Gestapo or the Stasi than anything ever envisioned by the 18th century liberals who shepherded America into existence.

Most interesting is the subtle psychological portrait of what kind of person seeks and keeps this kind of power, and what power does to this kind of person. It is a frightening feedback loop at work here. The worst get on top, as Hayek says, but the top makes the worst people even more corrupt than they would otherwise be.

The powerful man truly imagines that there is no real distinction between his personal interest and the interest of the cause he imagines himself to represent. He talks effortlessly about his own desires and and the desires of the people he imagines himself serving; they are one and the same. At the same time, these people can easily rationalize their own personal corruptions and private indiscretions as small and much-deserved rewards for their personal sacrifices.

Most telling are the final stages of the film where Hoover is growing ever more obviously old and feeble, but he, like all people who have held the golden ring too long, is tempted by the fantasy of earthly immortality. He cannot and will not see the end. And his dreams of holding on forever are assisted by a doctor who keeps him constantly full of medications designed to preserve his life as long as possible.

Even until the very end, people feared him, mainly because of the private files on powerful people that he is rumored to have kept in his office. But did he still control the world he created? That is unclear. He created and built an security-state empire and he continued showing up for work every day, and there is no question that he imagined that the fate of the world rested in his hands.

Everyone saluted him and made the right noises in his direction. At the same time, he had only one feeble friend, no real colleagues at the agency, and freely told others that he can no longer trust anyone at the agency. He had died professionally long before his body finally expired. Tributes that followed his death were perfunctory and short lived.

When he died, he was no one’s hero. But the monstrosity he built lived on with unchallenged jurisdiction over the lives of all Americans. The pathologies of this man became the pathologies of the entire nation-state. For the young people who need a primer in the rise and corruption of the U.S. central state in the 20th century, this film is worth a close viewing.