But what about the authors’ IP rights?

IP Law, TechnologyBut what about the authors’ IP rights? Read Post »

Opponents of intellectual property often point out that modern patent and copyright are purely legislated, artificial schemes. For anarcho-libertarians and libertarians opposed to legislation as a means of forming law, this is yet another stake in the heart of IP. (See my post The Mountain of IP Legislation, and my article “Legislation and Law in a Free Society.”)

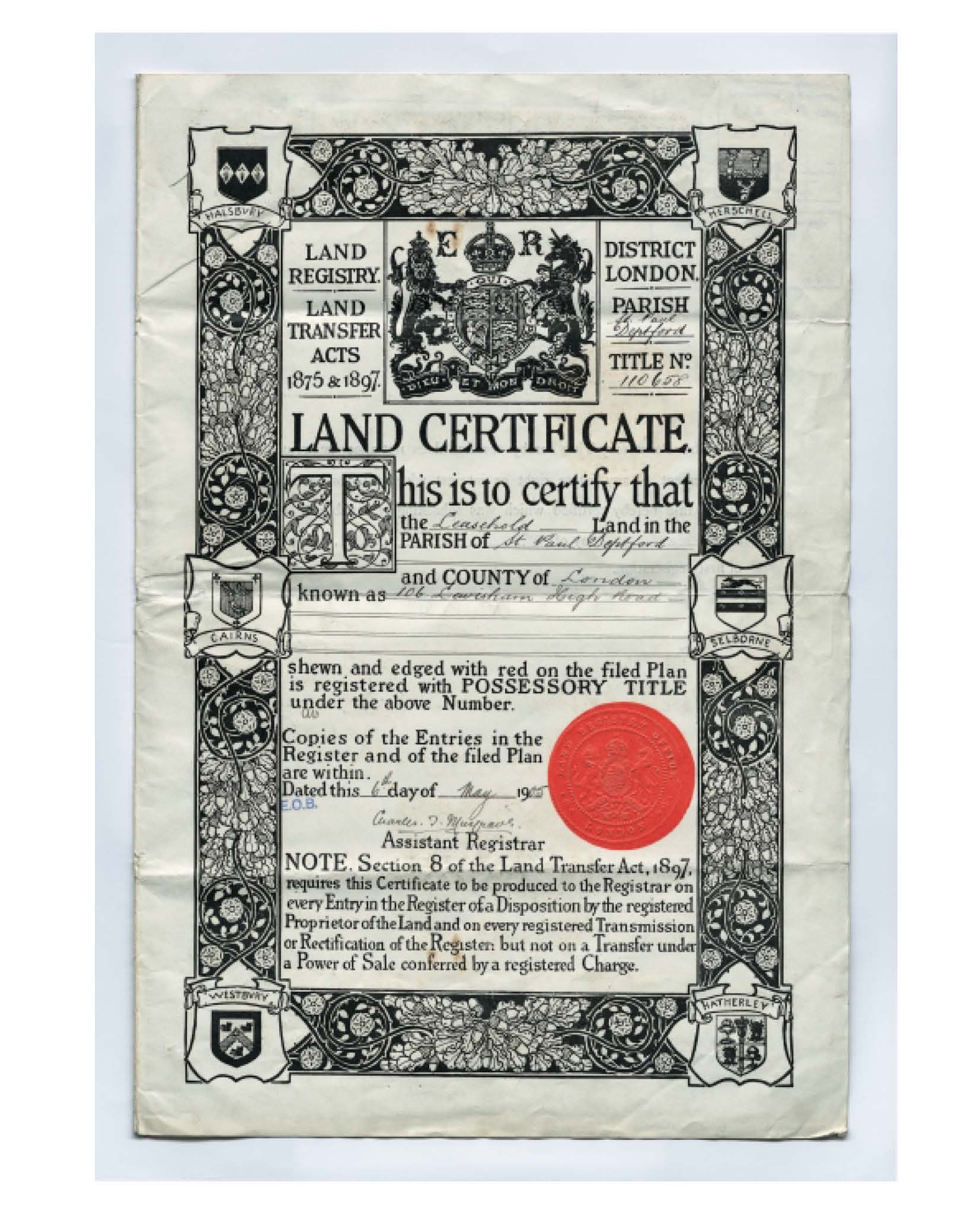

So it’s not surprising that one retort of the IPers is to argue that patent- and copyright-like rights “could” evolve in common law courts. Even though they didn’t; even though the idea of statutorily enacted schemes arising from judicial decisions is more than implausible: it’s ridiculous. Some of them simply posit that there could be private “title” offices in a free society akin to real property title records in use today: you just go down and “register” your “idea”; later, when you sue an “infringer” of “your” idea in court, you can prove you “own” it by introducing evidence from the IP title records office. For example, in a recent Mises blog threat, someone suggested there might be some private invention title office (my reply). And the anarcho-libertarian Tannehills, in their classic The Market for Liberty, argue (pp. 58-59):

Ideas in the form of inventions could also be claimed by registering all details of the invention in a privately owned “data bank.” Of course, the more specific an inventor was about the details of his invention, the thought processes he followed while working on it, and the ideas on which he built, the more firmly established his claim would be and the less would be the likelihood of someone else squeezing him out with a fake claim based on stolen data. The inventor, having registered his invention to establish his ownership of the idea(s), could then buy insurance (from either the data bank firm or an independent insurance company) against the theft and unauthorized commercial use of his invention by any other person. The insurance company would guarantee to stop the unauthorized commercial use of the invention and to fully compensate the inventor for any losses so incurred. Such insurance policies could be bought to cover varying periods of time, with the longer-term policies more expensive than the shorter-term ones. Policies covering an indefinitely long time-period (“from now on”) probably wouldn’t be economically feasible, but there might well be clauses allowing the inventor to re-insure his idea at the end of the life of his policy.

One problem with the Tannehills’ reasoning was the question-begging assumption that it’s “theft” to use an idea if it’s “unauthorized”; this presupposes there is property in information. …

Property Title Records and Insurance in a Free SocietyRead More »

Property Title Records and Insurance in a Free Society Read Post »

I was reading about the cool Mark Twain Google doodle here and was surprised to find that Google had actually managed to obtain a patent related to the idea of using homepage doodles. The inventor is Google’s co-founder Sergey Brin; the patent application was filed back in April 2001 but not granted as a patent until March 2011. The patent’s title is “Systems and methods for enticing users to access a web site” (PTO version; Google versionwith PDF). The abstract and claim 1 are below:

Abstract: A system provides a periodically changing story line and/or a special event company logo to entice users to access a web page. For the story line, the system may receive objects that tell a story according to the story line and successively provide the objects on the web page for predetermined or random amounts of time. For the special event company logo, the system may modify a standard company logo for a special event to create a special event logo, associate one or more search terms with the special event logo, and upload the special event logo to the web page. The system may then receive a user selection of the special event logo and provide search results relating to the special event.

Claim 1. A non-transitory computer-readable medium that stores instructions executable by one or more processors to perform a method for attracting users to a web page, comprising: instructions for creating a special event logo by modifying a standard company logo for a special event, where the instructions for creating the special event logo includes instructions for modifying the standard company logo with one or more animated images; instructions for associating a link or search results with the special event logo, the link identifying a document relating to the special event, the search results relating to the special event; instructions for uploading the special event logo to the web page; instructions for receiving a user selection of the special event logo; and instructions for providing the document relating to the special event or the search results relating to the special event based on the user selection.

This got me curious as to what other patents Brin might have obtained. Here they are (sigh):

Another search reveals 925 patents owned by Google (the thousands of patents acquired from Motorola Mobility are evidently not yet assigned to Google in the PTO database so don’t show up here), plus a bunch of pending patent applications.

You can’t really blame Google for playing the patent game and trying to build up a defensive patent portfolio.1 Still, asserting this patent against innocent companies would surely violate the company motto “Don’t be evil“.

[c4sif]

Not Being Evil? Google patents Google Doodles Read Post »

My monograph Against Intellectual Property, already translated into six other languages,1 is coming out in Czech (English version), by Mises.cz. Apparently the book will officially be launched at their Christmas libertarian meeting (hey, why don’t we have those over in America? sounds cool). Only libertarians could plan to celebrate a book about intellectual property at a Christmas party. Gotta love ’em.

Anyhoo, now my stuff is in 11 languages other than English. Kinda cool for a boy from Galvez, Louisiana. Actually, I visited Praha (Prague) while doing the backpacking thing in law school in 1990 or so, and my brother lived there for several years–once when I visited him in 1999, I was invited to give a speech (on Crime, Punishment and Restitution) at the Liberální institut by Josef Šíma, now of the Prague University of Economics and now also on the Editorial Board of my journal Libertarian Papers. So it’s nice to have my monograph coming out in Czech.

[C4SIF]

Georgian, German, Italian, Polish, Portugese, Spanish. ↩

Czech Mate on Intellectual Property Read Post »

One of my favorite podcasts, KERA’s “Think,” hosted by the excellent interviewer Kris Boyd, had a fascinating show recently, Beethoven and the World in 1824:

One of my favorite podcasts, KERA’s “Think,” hosted by the excellent interviewer Kris Boyd, had a fascinating show recently, Beethoven and the World in 1824:

What environment spawned one of the greatest orchestral compositions in history? We’ll find out this hour with music historian and New York Philharmonic Leonard Bernstein Scholar-In-Residence Harvey Sachs. His latest book is “The Ninth: Beethoven and the World in 1824? (Random House, Paperback, 2011).

As Sachs notes, the final movement of his famous Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, “Ode to Joy,” was innovative:

The symphony was the first example of a major composer using voices in a symphony (thus making it a choral symphony). The words are sung during the final movement by four vocal soloists and a chorus. They were taken from the “Ode to Joy“, a poem written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and revised in 1803, with additions made by the composer.

In other words, it was a remix, as most (all?) art is. In today’s hyper-copyright world, Schiller could stop Beethoven if he wanted, and prevented one of the greatest works of art of all time.

[C4SIF]

Beethoven: Remixer, Pirate Read Post »