The Nature of the State and Why Libertarians Hate It

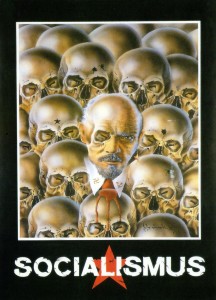

Anti-Statism, Libertarian Theory, Statism Rothbard described Mencken as “The Joyous Libertarian,” a label that could also be applied to Rothbard himself, called by Justin Raimondo “the happy scholar-warrior of liberty.” Yet Rothbard also famously said “hatred is my muse”. By this he meant, I think, hatred of the state and all manifestations of statism. Anti-statism is an essential aspect of libertarianism–anarchists oppose the entire state, root and branch, while minarchists oppose all of the modern state save for a tiny core of vital functions.

Rothbard described Mencken as “The Joyous Libertarian,” a label that could also be applied to Rothbard himself, called by Justin Raimondo “the happy scholar-warrior of liberty.” Yet Rothbard also famously said “hatred is my muse”. By this he meant, I think, hatred of the state and all manifestations of statism. Anti-statism is an essential aspect of libertarianism–anarchists oppose the entire state, root and branch, while minarchists oppose all of the modern state save for a tiny core of vital functions.

One of the most important thinkers on the nature of the state was Franz Oppenheimer, who distinguished between the economic means and the political means, and defined the state as the organization of the political means. As Hans-Hermann Hoppe explains in his superb Anarcho-Capitalism: An Annotated Bibliography:

Franz Oppenheimer is a left-anarchist German sociologist. In The State he distinguishes between the economic (peaceful and productive) and the political (coercive and parasitic) means of wealth acquisition, and explains the state as instrument of domination and exploitation.

As Oppenheimer wrote in his classic work The State:

I mean by [the “State”] that summation of privileges and dominating positions which are brought into being by extra economic power. And in contrast to this, I mean by Society, the totality of concepts of all purely natural relations and institutions between man and man …. [from the Introduction]

There are two fundamentally opposed means whereby man, requiring sustenance, is impelled to obtain the necessary means for satisfying his desires. These are work and robbery, one’s own labor and the forcible appropriation of the labor of others. … I propose … to call one’s own labor and the equivalent exchange of one’s own labor for the labor of others “the economic means” for the satisfaction of needs, while the unrequited appropriation of the labor of others will be called the “political means.” … The state is an organization of the political means. [Ch. 1]

Rothbard was also heavily influenced by Oppenheimer, writing in The Ethics of Liberty:

If the state, then, is a vast engine of institutionalized crime and aggression, the “organization of the political means” to wealth, then this means that the State is a criminal organization. …

The Nature of the State and Why Libertarians Hate ItRead More »

The Nature of the State and Why Libertarians Hate It Read Post »