Hedy Lamarr Bet on the Wrong Horse

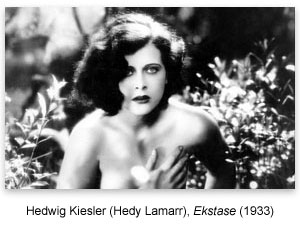

Business, Current Articles, History, Pop Culture, Science, Statism, Technology, War“Hedy stands naked in a field. She looks off-camera in dismay as her horse gallops away with the clothes she had draped over its back to take a dip in a woodland pond.”

That’s the opening line of my article “Putting Hedy Lamarr on Hold,” featured today in the Freeman.

I shared a draft with a writer friend of mine over the weekend. She is far more educated and literary than I am. She saw a parallel between the opening scene and the larger story that I confess I was not conscious of. I thought I’d just been going for sex appeal.

Here’s more of the opening:

She is not called Lamarr yet. That name will come later, in Hollywood. For now she is still Hedwig Kiesler, a Viennese teenager in Prague, playing her first starring role in a feature film, Ekstase (“Ecstasy,” 1933). The controversial Czechoslovakian film will become famous for Hedy’s nude scenes (which are not sexual) and its sex scenes (which show only her face, in close-up, in the throes of passion).

The film will give Hedy her first taste of fame. She will be known as the Ecstasy girl. An Austrian director will tell the press, “Hedy Kiesler is the most beautiful girl in the world.” Later, MGM movie mogul Louis B. Mayer will repeat the claim, using the name he insisted she change to: Hedy Lamarr.

But while the world of her time will remember her for her photogenic beauty, history will remember her as the inventor of frequency hopping, the foundational technology of today’s mobile phones and wireless Internet. [FULL ARTICLE]

The piece goes on to explain how Hedy invented frequency-hopping spread spectrum during World War II and why it took so long for that invention to usher in the wireless Internet age. Short answer: the government kept the technology secret for decades. Not only did Hedy Lamarr not see a cent from her invention; she didn’t even get credit for it until the end of the century.

The piece goes on to explain how Hedy invented frequency-hopping spread spectrum during World War II and why it took so long for that invention to usher in the wireless Internet age. Short answer: the government kept the technology secret for decades. Not only did Hedy Lamarr not see a cent from her invention; she didn’t even get credit for it until the end of the century.

So here’s what my writer friend said:

The more I think about it, the movie image you start with — Hedy looking at her runaway horse and thinking, ok now what? is exactly what you describe in your title: Hedy Lamarr on hold. She’s on hold in the movie (for a moment, I guess — given the movie title, I imagine that she’s not alone for long) and then her invention is on hold for a much longer time. … A Hollywood starlet and inventive genius who made millions in the market surrendered her most innovative idea to Leviathan, who stifled it. And she did so, ironically, because of a lack of imagination on her part — a naive faith that the state would protect and serve its citizens.

(By the way, I’m especially pleased that FEE decided not only to feature my article but also to use the image I put together for it!)

Hedy Lamarr Bet on the Wrong Horse Read Post »

My fixation on female national personifications continues:

My fixation on female national personifications continues: