On May 3, 2010, I gave a talk to a class of students studying public health policy at the University of Washington. I began the talk by asking the students how many of them believed that the current healthcare system in America was flawed; everyone in the class raised their hand. I then asked how many of them believed that the recently passed healthcare legislation, supported by President Obama, was a step in the right direction in reforming America’s healthcare system. Once again, everyone raised their hand.

While I agreed with the students on the first point, I disagreed that the recently passed legislation was a step in the right direction. My aim in giving the talk was to present the students with a consistent, libertarian, free-market perspective on healthcare reform, covering both the morality and the economics of why it would be desirable to eliminate government interference in the market.

The Morality of Healthcare Reform

One of the most important factors animating the libertarian rejection of public policy in general is the recognition that any state action must ultimately resort to the use or threat of aggression. As Ludwig von Mises observed,

It is important to remember that government interference always means either violent action or the threat of such action. Government is in the last resort the employment of armed men, of policemen, gendarmes, soldiers, prison guards, and hangmen. The essential feature of government is the enforcement of its decrees by beating, killing, and imprisoning.1

Libertarians who value justice and recognize that the use of aggression cannot be logically justified must reject all state action in principle — this includes the use of aggression in implementing healthcare policy.2

The Economics of Healthcare Reform

A common argument advanced in support of greater government intervention in the American healthcare market is that a large and growing fraction of the gross domestic product (GDP) is spent on healthcare, while the results, such as average life expectancy, do not compare favorably to the Western nations that have adopted some form of universal healthcare. This argument is spurious for two reasons:

- A growing fraction of GDP spent on healthcare is not a problem per se. In the early half of the 20th century, the fraction of GDP spent on healthcare grew significantly as new treatments, medical technology and drugs became available. Growth in spending of this nature is desirable if it satisfies consumer preferences.

- Attributing national-health results to the healthcare system adopted by different countries confuses correlation with causation and ignores the many salient variables that are causal factors affecting aggregate statistics (such as average life expectancy). Factors that are likely to be at least as important as the healthcare system include the dietary and exercise preferences of a population.

Another argument commonly used in healthcare-policy debates is that there are almost 46 million people who have no health insurance at all.3 Again, this is not a problem in and of itself. According to the National Health Interview Survey, 40 percent of those uninsured are less than 35 years old, while approximately 20 percent earn over $75,000 a year.4 In other words, a large fraction of those who are uninsured can afford insurance but choose not to buy it or are healthy enough that they don’t really need it (beyond, perhaps, catastrophic coverage).

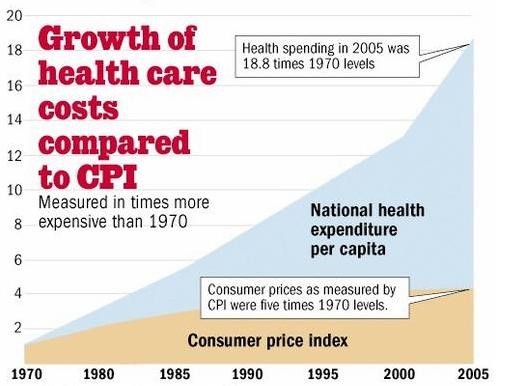

The real problem with the American healthcare system is that prices are continually rising, greatly outpacing the rate of inflation, making healthcare unaffordable to an ever-increasing fraction of the population — particularly those without insurance.

If prices in the healthcare market were falling, as they are in other markets such as computers and electronics, the large number of uninsured would be of little concern. Treatments, drugs, and medical technology would become more affordable over time, allowing patients to pay directly for them. Identifying the cause of rising healthcare costs should be the first priority for anyone who seeks solutions to America’s broken healthcare system.

As I explained to the students in the public-healthcare-policy class, there are four major causes of rising prices in the healthcare market, and in every case government intervention has either directly caused or greatly exacerbated the problem.

Employer-Provided Health Insurance

Perhaps the most important cause of rising healthcare prices in America is the employer-provided health-insurance system. The very existence of the system is itself a very strange occurrence and a big hint that government intervention played a key role in its creation. After all, employers do not pay for food or gasoline; why do they pay for healthcare?

Employer-provided health insurance has its origin in a tax policy passed in 1943, which made insurance provided by employers tax free. At the time the United States was engaged in World War II and had enacted wage and price controls,5 preventing employers from competing for scarce labor using the normal mechanism of offering a higher salary. Instead, businesses used the availability of newly tax-subsidized healthcare as a means of differentiating themselves.

The tax advantages were made even more attractive and fully codified in the 1954 Internal Revenue Code. Over the next few decades, the government’s subsidization of employer-provided health insurance lead to the dominance of that model of healthcare delivery, as the following data from the 1965 Sourcebook of Health Insurance Data makes clear.

The most important economic consequence of the existence of the employer-provided health insurance is that consumers are much less likely to discriminate on cost. Beyond the deductible, the employer pays the cost of medical procedures through an insurance company. As anyone who has gone on a business trip knows, if the company is paying, then the employee is likely to purchase a more expensive ticket and accommodation. Where an economy ticket may have sufficed for a personal budget, a business-class ticket becomes far more attractive.

Not only are consumers less likely to discriminate on cost, but providers of healthcare services have greater incentive to provide medical treatments that are only marginally more effective at much higher cost. This is the opposite of how the price mechanism works in a free market, where consumers (who are paying out of their own pocket) search for the cheapest prices and providers work hard to provide services that are equally efficacious but less costly.

The real problem with the American healthcare system is that prices are continually rising, greatly outpacing the rate of inflation, making healthcare unaffordable to an ever-increasing fraction of the population — particularly those without insurance.

While employer-provided health insurance undermined price sensitivity among consumers, it did not completely destroy it. Businesses, being profit-maximizing organizations, have an incentive to push back when costs increase. However, because of privacy concerns, businesses are less able to push back against rising healthcare than they are for plane tickets. An employer is less likely to pry into the cost effectiveness of a particular surgical procedure undertaken by an employee than they would be to pry into the purchase of a substantially more expensive first-class plane ticket.

In 1965, Medicare was passed as part of the Social Security Act, essentially supplying employer-provided health insurance to all citizens above the age of 65. However, the “employer” in this case was the US government, which does not have the same economic incentives as a business, but rather has political incentives. Elected officials have a strong incentive to promise their elderly constituents an expansion in the range of treatments covered by Medicare, as well as to lower the deductible that Medicare consumers pay out of their own pocket. Both these factors further undermine a consumer’s desire to discriminate on cost when seeking medical treatments.

In 1960, the government covered 21 percent of total medical expenditures with 55 percent coming out of consumer pockets. In 2000, 43 percent were covered by the government with 17 percent coming out of pocket. Unsurprisingly, the passing of Medicare in 1965 almost immediately lead to a precipitous rise in US healthcare spending as a fraction of GDP.

While price sensitivity has widely been undermined in the American healthcare system,  there remain some exceptions to the rule, where the normal market mechanism remains intact. I gave two examples to the students of how price sensitivity is working in healthcare today in order to illustrate how it would work in a free market.

there remain some exceptions to the rule, where the normal market mechanism remains intact. I gave two examples to the students of how price sensitivity is working in healthcare today in order to illustrate how it would work in a free market.

The first example was the LASIK corrective-vision procedure, which has become very popular over the last decade. LASIK is an elective procedure that is not covered by standard insurance, and consumers must pay directly for the service — which means that they are much more likely to discriminate between providers both on cost and reported quality of the surgeon. With these incentives in place, the LASIK procedure has been reported to have fallen in cost by over 30 percent during the last decade.6

Even more importantly, the quality of the procedure has improved dramatically in that period as providers competed to deliver the most efficacious treatment. According to Erik Gross, an expert in the field of LASIK technology,

Early procedures were not LASIK at all, but uncomfortable surface ablations with no astigmatism correction. Subsequent generations of the procedure increased the treatable range, added correction for astigmatism, correction for hyperopia, the lasikflap to increase stability and comfort, accuracy and safety features, and finally moved to true custom wavefront analysis and correction.7

The second example I gave the students was from a personal experience, when I wanted to have a small epidermoid cyst removed from my back. The first practice I visited was a dermatologist’s office, which deals primarily with insured customers and can afford to charge exorbitant rates. I explained to the assistant on my first consulting visit that I didn’t have health insurance — I choose not to — and asked how much the procedure would cost if I paid cash. She quoted me $700 for a riskless procedure that takes about 15 to 20 minutes to perform, and would not in this instance be performed by the dermatologist, but by the assistant herself. As I explained to the students in the public-health-policy class, the fact that there are very basic procedures that cost the equivalent of $2,100 an hour is a glaring sign that the market’s normal price mechanism has been broken.

On the recommendation of a friend, I decided to visit another medical practice, Country Doctor, which deals mostly with lower-income patients who do not have health insurance. Because its customers pay out of pocket, Country Doctor has a much stronger incentive to charge prices that its customers are willing to pay up front. When I had the procedure to remove the cyst done at Country Doctor, it was performed by an actual doctor, and it cost less than $50.

The moral of the story is that price sensitivity is a crucial factor in driving prices down over time. Government policy has undermined price sensitivity, and this has been a very important cause in the rising costs of the American healthcare system.

Licensure

Licensure is the practice of restricting entry into a market by forcing practitioners and providers to seek permission before doing so. A common fallacy is that medical licensure protects consumers — yet having a license is no assurance of the ability of a person to practice medicine. Some who have received their license decades ago may no longer be fit to practice, demonstrated either by incompetence or lack of continued education.

The fact that there are very basic procedures that cost the equivalent of $2,100 an hour is a glaring sign that the market’s normal price mechanism has been broken.

From its inception, the practice of licensure has been motivated primarily by the control of supply by organized medicine — in particular, the American Medical Association (AMA) — to allow the increase of wages for members of the licensed group. In the early 20th century, for instance, a physician named J.N. McCormack spent several years traveling the United States on behalf of the American Medical Association in an attempt to convince doctors of “The Danger to the Public from an Unorganized and Underpaid Medical Profession.”8

The restriction of supply and the attendant rise in prices faced by consumers is not the only detrimental factor that can be attributed to the actions of the AMA. As Milton Friedman pointed out,

It is clear that licensure is the key to the medical profession’s ability to restrict the number of physicians who practice medicine. It is also the key to its ability to restrict technological and organizational changes in the way medicine is conducted.9

In other words, the AMA has sought not only to limit supply, but also to regulate who can practice various aspects of medicine. For instance, many medical procedures and decisions about prescriptions could be handled by nurses or medical technicians rather than doctors, whose labor is more expensive. Licensure limits the extent to which market forces — that is, forces that lead to the cheapest and most effective results for consumers — may determine the most efficient use of doctors, nurses, and technicians.

A recent example of the AMA’s use of licensure was their attempt — ostensibly for “patient safety,” — to regulate Walmart’s creation of low-cost retail clinics by preventing the clinics from operating using only nurse practioners.10 The practioners would have only been providing very basic medical services, such as administering needles and prescribing drugs, which Van Ruth et al. conclude carries no extra risk to patients.11

It is precisely the sort of clinics operated by Walmart that allow consumers — and especially the poorest in society — access to basic, affordable healthcare. By regulating these clinics and reducing the supply of doctors and providers, the AMA has caused higher prices for American consumers of healthcare.

The Obesity Epidemic

In terms of its cost, obesity is perhaps the largest medical problem in America. Finklestein et al. estimate that medical expenditures for treatment of patients who are either overweight or obese accounted for almost 10 percent of all medical expenditures in 1998, at a cost of 92 billion dollars (in 2002 inflation-adjusted dollars).12 They also estimate that almost half of all Americans are either overweight or obese, with the numbers in each category growing by 70 percent and 12 percent, respectively, during the decade prior to 2003. Sturm estimates that obese adults incur annual medical expenditures that are 36 percent higher than those of normal weight incur.13

It is precisely the sort of clinics operated by Walmart that allow consumers — and especially the poorest in society — access to basic, affordable healthcare.

One might conclude from these statistics that obesity in America is a clear example of a failure of the free market — that undirected consumers, without the protection of a benevolent government agency, have taken to consuming increasingly high-calorie and unhealthy foods, leading to America’s obesity epidemic. However, this specious (yet popular) narrative is contrary to the facts and disregards the crucial role government policy has played in encouraging the production of unhealthy foods supplied to American consumers.

Recent research has uncovered the baneful influence that corn-based sweeteners have had on America’s obesity epidemic. It is estimated that Americans consume 73 pounds of corn-derived sweetener per person per year,14 and as Michael Pollan points out, the growth of corn-based sweeteners is a direct result of the government’s farm policy, which subsidizes corn production.15 A basic consequence of economic law is that when something is subsidized, more of it will be produced. Pollan writes,

Very simply, we subsidize high-fructose corn syrup in this country, but not carrots. While the surgeon general is raising alarms over the epidemic of obesity, the president is signing farm bills designed to keep the river of cheap corn flowing, guaranteeing that the cheapest calories in the supermarket will continue to be the unhealthiest.

Pollan also correctly notes that the calories from high-fructose corn syrup are unhealthier than those from natural sweeteners such as sugar. Research by Powell et al. concludes that “[r]ats with access to high-fructose corn syrup gained significantly more weight than those with access to table sugar, even when their overall caloric intake was the same.”16 Avena, commenting on their study, said that “[o]ur findings lend support to the theory that the excessive consumption of high-fructose corn syrup found in many beverages may be an important factor in the obesity epidemic.”

The obesity epidemic in America has been exacerbated by the abundance and relative cheapness of high-fructose corn syrup. The growth of calories produced, and in particular the abundance of unhealthy calories, is not an outcome of the free market but rather the direct — if perhaps unintended — consequence of government farm policy. As Pollan observes,

Since 1977 an American’s average daily intake of calories has jumped by more than 10 percent…. This was, of course, the same decade that America embraced a cheap-food farm policy…. Since the Nixon administration, farmers in the United States have managed to produce 500 additional calories per person every day.17

Only by removing the subsidies available to corn producers, and allowing local and organic farmers to compete on an even playing field, will healthier calories become more economically attractive to consumers.

Intellectual Property

A patent is a government-granted monopoly on production. Holders of pharmaceutical patents are free of the strictures of competition when deciding the price at which to sell the drugs they produce. In practice this means that drug companies are able to charge significantly higher prices than they could in a market free of government intervention. Kesselheim et al. estimate that for three drugs alone (amoxicillin, metformin, and omeprazole), the delayed availability of generic alternatives cost Medicaid 1.5 billion dollars between 2000 and 2004.18

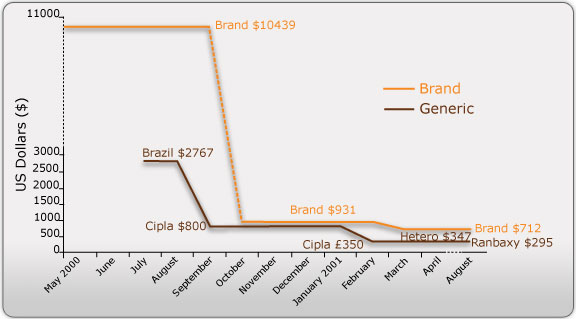

The following chart illustrates the effect of generic competition on the price of a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs, used to treat HIV, between 2000 and 2001.19

Before the availability of a generic competitor the brand cocktail cost over $10,000. Once generic competition was introduced, the price rapidly dropped to $712. The dramatic difference in cost hardly covers the human cost of government-granted monopolies on drug production — namely, the tens of thousands infected with HIV who died for want of affordable treatment.

One common myth in the economics profession is that intellectual-property rights are necessary to foster innovation in the production of ideas. Recent work by Boldrin and Levine20 and Stephan Kinsella21 has exploded the fallacies underpinning this widely believed economic shibboleth.

In particular, Boldrin and Levine devote a chapter of their book, Against Intellectual Monopoly, to the pharmaceutical industry. They argue that the actual cost of bringing drugs to market is substantially lower than the estimates suggested by studies conducted by the pharmaceutical industry — a group with a vested interest in lobbying for strong patent protections. They also provide evidence that in many instances the existence of patents hinders research in drug production.

Patents are not a natural outcome of the free market but are government-granted monopolies on production. Contrary to conventional economic wisdom, patents are not an unequivocal benefit in fostering the development of ideas. The existence of patents is, on the contrary, a clear contributor to the high cost of medical treatments available to American consumers.

Conclusion

In giving the talk to the class of public-health students, my aim was to disabuse them of the widely held belief that America’s healthcare system is an example of a free-market failure and that a free market in healthcare compares poorly to that of government-provided, universal care. In fact, the US healthcare system has endured substantial government intervention — albeit intervention of a different variety than that of Europe or Canada. And the areas in which the government has intervened in the market have seen substantial increases to costs for consumers.

None of the causes of higher prices identified in this essay are adequately addressed by the recently passed healthcare legislation. Indeed, the problem of high costs will be further exacerbated by extending insurance to cover more people and more procedures while also reducing deductibles.

The only solution to increasing costs is to eliminate government interference in the market and to allow the price mechanism to work as it should. Consumers who pay out of their own pocket will search for the cheapest solutions to suit their needs, while providers of healthcare will compete, through constant innovation, to drive prices down and discover the most efficacious treatments.22

[This article is also available at Mises.org]

Ludwig von Mises, Economic Freedom and Interventionism (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006), p. 15. ↩

For a discussion of the logical justification of libertarian morality, see Hans-Herman Hoppe, The Economics and Ethics of Private Property: Studies in Political Economy and Philosophy (Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006), ch. 13. ↩

Carmen DeNavas-Walt, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith, “Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008,” p. 27.

↩

↩For a summary of the National Health Institute Survey, see here. ↩

“Compensation from World War II through the Great Society,” Bureau of Labor Statistics. ↩

This paragraph comes from my personal correspondence with Erik Gross, formerly an engineer with Visx, AMO, and Abott labs, who worked on many of the improvements to LASIK mentioned. ↩

Illinois Medical Journal, vol. 9 (Springfield: The Illinois State Medical Society, 1906), pp. 260–2. ↩

Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Fortieth Anniversary Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 154. ↩

Meg Marco, “American Medical Assocaition Goes After Walmart-Style Retail Clinics,” The Consumerist. ↩

L.M. Van Ruth, P. Mistiaen, and A.L. Francke, “Effects Of Nurse Prescribing Of Medication: A Systematic Review,” The Internet Journal of Healthcare Administration, vol. 5 no. 2 (2008). ↩

Eric A. Finkelstein, Ian C. Fiebelkorn, Guijing Wang, “National Medical Spending Attributable to Overweight and Obesity: How Much, And Who’s Paying?” Health Affairs (2003). ↩

R. Sturm, “The Effects of Obesity, Smoking, and Drinking on Medical Problems and Costs,” Health Affairs (March/April 2002): p. 245–53. ↩

“Sugarcane Profile,” Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. ↩

Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma (New York: Penguin, 2006), p. 108. ↩

M.E. Bocarsly, E.S. Powell, N.M. Avena, and B.G. Hoebel, “High-fructose corn syrup causes characteristics of obesity in rats: Increased body weight, body fat and triglyceride levels,” Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior (2010). ↩

Omnivore’s Dilemma, pp. 102–3 ↩

Aaron S. Kesselheim, Michael A. Fischer, and Jerry Avorn, “Extensions Of Intellectual Property Rights And Delayed Adoption Of Generic Drugs: Effects On Medicaid Spending,”Health Affairs 25 no. 6 (2006): 1637–47. ↩

“AIDS, Drug Prices, and Generic Drugs,” AVERT. ↩

Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, Against Intellectual Monopoly (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005). ↩

N. Stephan Kinsella, Against Intellectual Property (Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008). ↩

I would like to thank my friend Amy Iacopi for her original invitation to speak to the public-health-policy class, and Professor Doug Conrad and his students for being so welcoming and open to considering a perspective on healthcare different from their own. I was pleased, and a little surprised, that after giving the talk most of the questions the students had focused on the morality of a free market (since I had only devoted a small portion of the talk to issue of morality and spent most of it on the economics) and how a purely voluntary society might function in practice. I would also like to thank my friend Jon Perlow, whose brilliant essay, “Government, Free Markets, and Healthcare,” was the original motivation for my talk. ↩