Last month, I mentioned America’s first individualist anarchist, Anne Hutchinson. She’s a hero of mine, for obvious reasons, despite my not sharing her religious beliefs.

Last month, I mentioned America’s first individualist anarchist, Anne Hutchinson. She’s a hero of mine, for obvious reasons, despite my not sharing her religious beliefs.

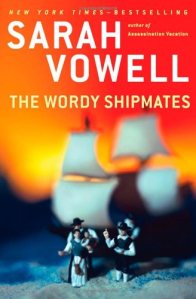

One of the several reasons I’m enjoying Sarah Vowell’s The Wordy Shipmates is that I’m learning more about Hutchinson. For example, I love this detail:

The daughter of a persecuted Puritan minister who helped her cobble together the best education possible for female children (who were denied university attendance), Anne Hutchinson is one of the brainiest English-women of the seventeenth century. Yet she is no stranger to the goopy fluids of female biology. Besides birthing her own litter [of 15 children, by the way!], she works as a midwife, delivering babies and no doubt serving the brew imbibed before and after labor, the wonderfully named “groaning beer.”

Here’s my favorite detail within the detail:

By aiding Boston’s new mothers, Hutchinson quickly befriends a lot of women. She starts leading the women in a regular Bible study in her large, fine home.

These Bible-study group became the seedbed of antinomianism: a new religious individualism (and heresy) within New England Puritanism. It also became the basis of political and philosophical individualism more generally, thus Murray Rothbard’s description of Hutchinson in Conceived in Liberty as America’s first individualist anarchist.

She preached the necessity for an inner light to come to any individual chosen as one of God’s elect. Such talk marked her as far more of a religious individualist than the Massachusetts leaders. Salvation came only through a covenant of grace emerging from the inner light, and was not at all revealed in a covenant of works, the essence of which is good works on earth. This meant that the fanatically ascetic sanctification imposed by the Puritans was no evidence whatever that one was of the elect. Furthermore, Anne Hutchinson made it plain that she regarded many Puritan leaders as not of the elect.

The Massachusetts powers that be understood that Hutchinson’s Bible-study sessions were central to the dissemination of her religious and political heresies and so, as Sarah Vowell relates,

In September of 1637 … [t]hey resolve, writes Winthrop, “That though women might meet (some few together) to pray and edify one another,” assemblies of “sixty or more” as were then taking place in Boston at the home of “one woman” who had had the gall to go about “resolving questions of doctrine and expounding scripture” are not allowed.

"The Bill of Rights," Vowell comments, "with its allowance for freedom of assembly, is a long way off."

Rothbard again:

Winthrop then called for a vote that Mrs. Hutchinson “is unfit for our society — and … that she shall be banished out of our liberties and imprisoned till she be sent away.…” Only two members voted against her banishment.

When Winthrop pronounced the sentence of banishment Anne Hutchinson courageously asked: “I desire to know wherefore I am banished.”

Winthrop refused to answer: “Say no more. The court knows wherefore, and is satisfied.” It was apparently enough for the court to be satisfied; no justification before the bar of reason, natural justice, or the public was deemed necessary.

As good as Rothbard’s account is, I find Vowell’s even better:

As good as Rothbard’s account is, I find Vowell’s even better:

“What law have I broken?” she asks.

“Why the fifth commandment,” answers Winthrop. This is of course the favorite commandment of all ministers and magistrates, the one demanding a person should honor his father and mother, which for Winthrop includes all authority figures. Wheelwright’s sermon was an affront to the fathers of the church and the fathers of the commonwealth.…

When she presses him once again to point out the Scripture that contradicts the Scripture she has quoted calling for elders to mentor younger women, Winthrop, flustered, barks, “We are your judges, and not you ours.”

Winthrop really is no match for Hutchinson’s logic. Most of his answers to her challenges boil down to “Because I said so.”

In fact, before this trial started, the colony’s elders had agreed to raise four hundred pounds to build a college but hadn’t gotten around to doing anything about it. After Hutchinson’s trial, they got cracking immediately and founded Harvard so as to prevent random, home-schooled female maniacs from outwitting magistrates in open court and seducing colonists, even male ones, into strange opinions. Thanks in part to Hutchinson, the young men of Massachusetts will receive a proper, orthodox theological education grounded in the rigorous study of Hebrew and Greek.

The US attorney general recently announced that homeschooling is not a fundamental right, thereby denying asylum to a German family that had fled their home country, where the 1938 Nazi-introduced ban on home education is still enforced. The American homeschooling community is understandably outraged at the current presidential administration’s position on the question, but we shouldn’t be at all surprised. Why would any government willingly relinquish the authority to indoctrinate? The need to prevent random, homeschooled maniacs from outwitting political leaders and seducing citizens into strange opinions — such as individual freedom and responsibility — is essential to the health of the state. And if we question too vociferously the logic of their decision, they may well reply in essence that they are our judges and not we theirs.