Are there any major differences between American and British science fiction (SF)? If so, what are they and what is the reason for them? What the heck does this have to do with libertarianism?

In the December 2007 issue of Locus Magazine, reviewer Graham Sleight says a couple of interesting things about the differences between American and British SF:

One of the interesting tensions in [Greg] Bear’s work is between the American and British strains of SF. Broadly (and here I’m borrowing from Brian Stableford’s The Scientific Romance in Britain (1985)), British SF derives from the scientific romance tradition of Wells and Stapledon, in which protagonists observe (often in wonder) but do not change the world. In American SF, they do, and the future is something to be worked on, conquered, perhaps owned.

I definitely have a greater affinity for the American strain. The British strain seems to lend itself well to cynical or satirical dystopian stories; the American strain more likely to be hopeful and productive of a libertarian future. The work of Robert Heinlein, one of my favorite science fiction authors, is quintessentially American. Ayn Rand’s Anthem and Atlas Shrugged are a dystopian novella and novel, respectively, with distinctly American endings.

In a sense, [Alastair] Reynolds’s book [Revelation Space (2000)] should be seen here as emblematic of what other British writers have been doing recently: taking the props of American SF and putting a distinctive dark perspective on them. . . . The end of the book opens up the sort of cosmological perspectives one associates with Stapledon (or Baxter), but does so in a story where individual actions make a difference.

I’m not a huge fan of the cosmological-perspective stories in which individual actions make little or no difference. They can be dreadfully pessimistic and dark. And while a cosmological perspective, used in moderation, can offer us a wider perspective on the present and our own individual concerns, it is a mistake to think that this perspective is primary for telling/showing us what is really important and valuable. I think some SF authors make this mistake. Is it a distinctively British one? Not that I’m indicting all of British SF, mind you — just making an observation about general tendencies and parallels.

I think a proper ethics approaches value (and virtue) from an agent-relative, interested, first-person perspective (i.e. a praxeological one) rather than from a typically modern, agent-neutral, impersonal, third-person perspective. I have in mind particularly an ethics focused on the principles necessary for the self-perfection and flourishing of the individual as opposed to the typically modern, rule-oriented approach in which the individual moral agent gets lost amidst social duties to attend to the needs of others. The focus on the cosmological perspective in science fiction, with its passivity and tendency to dwarf the stature of man, strikes me as being related to the modern, impersonal approach to ethics.

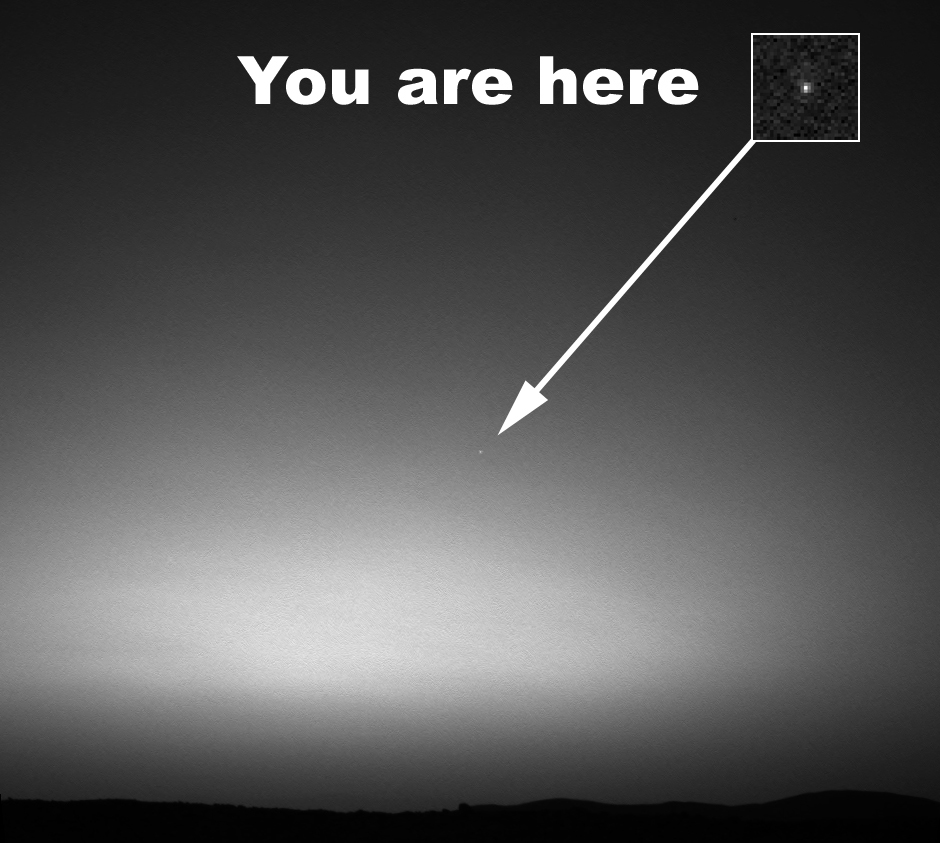

It reminds me also of the purposeful attempts to belittle man, to diminish the importance of individual values and achievements, by pointing to a photograph of our galaxy, or conjuring a mental image of the universe, and exclaiming how small the earth is amidst all that vastness — “We’re just insignificant specks in the grand scheme of things after all.” — the implications often being anti-individualist and unlibertarian.1

What does breaking a few paltry eggs matter when one must make an omelette? As I discussed in my previous post, reviewing the movie Ninja Assassin, collectivist political philosophies rely upon this diminution and subordination of individual human beings.2 Libertarianism, on the other hand, is an inherently individualist political philosophy, recognizing the importance and value of the individual. Consistent respect for the rights to life, liberty, and property of others represents the recognition that they are ends-in-themselves, not means to our ends or those of Society, the State, or the Cosmos. Our lives and achievements have value. They have value to us, even to others. That is all that really matters — yes, even in the grand scheme of things. And the universe is here not just to be passively observed, but to be transformed into goods for the betterment of our lives.

[Note: This is a revised and expanded version of an older post at Is-Ought GAP.]

Regarding the right perspective mentioned in the image caption, see This Picture of Earth from Mars is the Most Amazing Thing Ever. EVER. ↩

Somewhat paradoxically, the very same people who seem to take pleasure in pointing out our insignificance often turn right around and proclaim that we are destroying our planet and we must take drastic action now! I say this not to belittle real environmental concerns that directly and adversely affect people and their property but to point out certain tendencies, contradictions, and hypocrisies. ↩

The focus on the cosmological perspective in science fiction, with its passivity and tendency to dwarf the stature of man, strikes me as being related to the modern, impersonal approach to ethics.

I’m disappointed by this statement.

The cosmological (or even geological) perspective is one that we ought to treasure. After all, we are the only species we know about which is able to appreciate it.

And we ought to recognize along the way that we are small. And, combined with the fact that we’re the only cosmological-scale-perceiving beings we yet know of, we ought to do everything in our power to make sure that we don’t screw up royally.

None of this is to diminish human nature, or to suggest that humanity is insignificant or that an individualist perspective ought be sacrificed in favor of a galactic or universal one. For me, it suggests that an integration of the personal and the universal is necessary, if we are to understand who we are. And, really, I find that awesome.

Hi Mike,

I think this statement:

…needs to be read in context with this one:

…and that may clear up your objection.

Where would you put Ken MacLeod’s fiction in terms of these categories? The main characters in the Fall Revolution stories do change the world, and do so quite drastically sometimes, but they do it against the background of massive changes going on that are far beyond their control.

Well, Roderick, I think as the second quote from Graham Sleight suggests that the two approaches/perspectives aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive — that they make up two poles on a continuum. I think either extreme can be problematic and be executed poorly. And it is possible to combine the two, at least to some degree. MacLeod is someone I need to read more of, admittedly; but it was never my argument that all authors could be neatly pigeonholed into one or the other. I was rather speculating about the general, perceived tendencies of two large geographic groups of writers, then using that as a springboard to make observations about what seem to me to be similar perspectives in ethics and politics. From what I have read, MacLeod’s fiction strikes a more realistic balance. I merely worry about and am generally turned off by an excessive focus on the cosmological perspective, especially when it causes us to lose sight of the individual, personal perspective (intentionally or not) that I think is and should be primary. To switch to a different medium of expression, if “all we are is dust in the wind,” what does any of the good we do, our values, our achievements, being virtuous, avoiding vice – what does it all really matter? What’s the point? Why bother? There’s a danger of going too far down that road and getting lost.