When I was in 5th grade, the teacher, Mr. Kelly, asked the class if anyone could tell him the definition of the word twilight. I raised my hand, excited to know the answer for once: “A dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind — a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination…”

When I was in 5th grade, the teacher, Mr. Kelly, asked the class if anyone could tell him the definition of the word twilight. I raised my hand, excited to know the answer for once: “A dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind — a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination…”

“You idiot!” interrupted Mr. Kelly. (Does the setting of New York City in the 1970s explain at all why the teacher talked to his pupils that way?) “That’s the Twilight Zone! — Twilight is the period between sunset and darkness…”

Oh, I thought. So that’s why the show is called the Twilight Zone. It’s an in-between thing.

I wonder if there are kids today who will some day tell a similar story — probably with a less ill-mannered teacher — where they answer the vocabulary question by stating that “twilight” is when high-school vampires are in love with teenage mortals.

When I was a kid, The Twilight Zone was the smartest television show I watched. And I watched a lot of TV. It had already been off the air for a decade, but so had most of my shows. I grew up in the 1970s watching the TV of the 1950s and ’60s on a portable black-and-white television set with antennas made of coat hangers and tinfoil.

I loved the plot twists, and I didn’t mind all the moralizing. Most of the television I watched was preachy — and kids are used to being preached at from all directions, not just their TV viewing — but unlike all the other shows I watched, The Twilight Zone dealt with mind-bending ideas, and its plots weren’t predictable, at least not to me. Each episode ended with a revelation, and I enjoyed trying to guess what it would be, though I seldom guessed right.

The critics had loved it from the beginning — well before the show became popular with viewers — and later critics ranked it as a high point in television history:

In 1997, the episodes “To Serve Man” and “It’s a Good Life” were respectively ranked at 11 and 31 on TV Guide‘s 100 Greatest Episodes of All Time.…

In 2002, The Twilight Zone was ranked No. 26 on TV Guide‘s 50 Greatest TV Shows of All Time. In 2013, the Writers Guild of America ranked it as the third best written TV series ever. (Wikipedia)

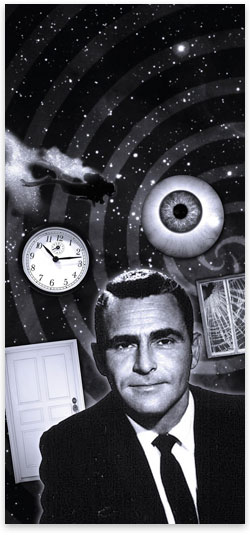

The show’s creator, executive producer, and head writer, Rod Serling was one of the star television writers from the first “Golden Age of Television.”

His successful teleplays included Patterns (for Kraft Television Theater) and Requiem for a Heavyweight (for Playhouse 90), but constant changes and edits made by the networks and sponsors frustrated Serling. In Requiem for a Heavyweight, the line “Got a match?” had to be struck because the sponsor sold lighters; other programs had similar striking of words that might remind viewers of competitors to the sponsor, including one case in which the sponsor, Ford Motor Company, had the Chrysler Building removed from a picture of the New York City skyline. (Wikipedia, “The Twilight Zone”)

In the Golden Age of Television, sponsors not only attached their names to the TV shows they sponsored — Kraft Television Theater, Philco TV Playhouse, Goodyear TV Playhouse, The Alcoa Hour, The Voice of Firestone, The US Steel Hour — they developed shows, produced them, and paid the networks to put them on the air.

Robert J. Thompson, a communications professor at Syracuse University, writes,

Robert J. Thompson, a communications professor at Syracuse University, writes,

This arrangement led to some legendary stories of sponsor interference. Alcoa, manufacturers of aluminum, for example, would not let Reginald Rose set a tragic event in his episode of The Alcoa Hour in a trailer park, where most of the homes are made of aluminum. The Mars company, which sponsored Circus Boy, made it known to those making the show that they didn’t appreciate references in the program to ice cream, cookies, or other treats that competed with Mars’s candy products for the sweet tooth of America’s youth.

And for those of you who’ve read my earlier post “Who destroyed the first golden age of television?” take note of this one:

In “Judgment at Nuremberg,” an episode of Playhouse 90, about the trials of Nazi war criminals, a reference to “gas chambers” was deleted by the sponsor, the American Gas Association. (Television’s Second Gold Age)

Two years before Serling created The Twilight Zone, he wrote a long introduction to a paperback release of his historic teleplay Patterns. (“Many of the scripts for these [1950s TV] plays were collected and sold in book form,” writes Professor Thompson, “a distinction prime-time programs would not enjoy again for many years.”)

In his introduction, Serling reviews the history of television drama and his career in the medium, gives advice to young writers, and voices his regret about the medium’s dependence on commercial interruptions and busybody sponsors.

For good or for bad, the television play must ride piggy-back on the commercial product. It serves primarily as the sugar to sweeten the usually unpalatable sales pitch. It’s the excuse to wangle and hold an audience.

Serling is clearly trying for a measured tone in that introduction. In Submitted for Your Approval, a documentary about his career released 20 years after his death, we get a more candid opinion:

How can you put out a meaningful drama when every fifteen minutes proceedings are interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits with toilet paper?

Still, Serling understood that his career depended on the dancing rabbits:

A sponsor invests heavily in television as an organ of dissemination. That organ would wither away without his capital and without his support. In many ways he hinders its development and its refinement, but by his presence he guarantees its survival. (Patterns, introduction)

In addition to specific cuts and changes, the TV sponsors of the 1950s had informal rules limiting content. While Serling was already known as a writer of television drama, The Twilight Zone made him famous ever after for fantasy and science fiction. In his 1957 introduction to Patterns, you can already see him being pushed in that direction as a reaction to the sponsors’ fiats:

One of the edicts that comes down from the Mount Sinai of Advertisers Row is that at no time in a political drama must a speech or character be equated with an existing political party or current political problems.

Serling’s 1956 teleplay about the US Senate was gutted. Several million television viewers tuned in to his political drama “The Arena,” Serling writes, and

were treated to an incredible display on the floor of the United States Senate of groups of Senators shouting, gesticulating and talking in hieroglyphics about make-believe issues, using invented terminology, in a kind of prolonged, unbelievable double-talk.

“In retrospect,” Serling mused,

I probably would have had a much more adult play had I made it science fiction, put it in the year 2057, and peopled the Senate with robots. This would probably have been more reasonable and no less dramatically incisive.

Serling insists that he did not make trouble: “I’m considered to be a cooperative writer — even now. I don’t get my back up at requests for rewrites.” But he was known in the industry as the “angry young man of Hollywood,” and when he died of a heart attack at age 50, many newspapers “mentioned that he had been a heavy smoker for years and was angry and stressed most of his life” (Wikipedia).

But while he fought television executives and sponsors over what he unfortunately called “censorship” (see my post “censorship schmensorship” on why this label is misleading, at best), he fell short, in the 1950s at least, of proposing government intervention — or any other specific solution:

I don’t really believe there exists a “good” form of commercial. There are some that are less distasteful than others, but at best they’re intrusive.… I make reference to this by way of pointing out a basic weakness of the medium. I do not presume to suggest any antidotes or alternatives. At the moment none seems possible. (Patterns, introduction)

Sadly, by the ’60s, he was willing to call on the state. According to a 1964 article about Rod Serling and “TV censorship,” we learn that Serling

proposed that the Federal Communications Commission “pass muster” in some fashion on the quality of advertising in television. The FCC has never been a “strong arm of the government” because it was afraid of being accused of censorship, he said. (“Serling Rips TV Censorship,” Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin, May 1, 1964)

Note the irony of his fighting the “censorship” of private editorial policies within the networks, then dismissing concerns about the real-deal coercive variety from the central government.

There’s another irony to Serling’s shift. You need to note the dates and know a little television history to catch it.

The television industry in which Rod Serling had established his name was dominated by sponsors — this was precisely Serling’s problem with it:

No dramatic art form should be dictated and controlled by men whose training and instincts are cut of an entirely different cloth. The fact remains that these gentlemen sell consumer goods, not an art form. (Submitted for Your Approval)

And yet the era of Serling’s ascendancy is now considered the Golden Age of Television and the TV drama of the era is recognized as an art form at its peak (until the present new golden age of television drama came to surpass it). According to television producer Sherwood Schwartz, the success of that earlier era resulted directly from its domination by the sponsors:

[T]he networks were conduits and they had no control of programming. Sponsors had more power, and the creative people who created the shows had more authority.

Professor Thompson indicates other benefits of the 1950s arrangement:

[S]ingle sponsorship also had advantages. R.D. Heldenfels, TV critic and author of Television’s Greatest Year: 1954, points out that “Unlike the current system, where a terribly low-rated show is pulled after one or two telecasts, a single sponsor willing to wait for good numbers — or to settle for lower numbers because the show increased the sponsor’s prestige — could keep a show going.” Since networks made money as long as the show remained sponsored, the only reason for them to cancel a sponsored series was if the ratings were so low that they threatened to reduce the size of the potential audience for the next show on the schedule. Indeed, many companies were more concerned with prestige than they were with numbers. If not for prestige, why would a company like US Steel have sponsored an anthology? There were no raw US Steel products that a mass audience could buy over the counter and most viewers had no idea where the steel in their automobiles came from. It was even possible that a show would continue to be sponsored based on the tastes of a single executive or company owner. The classical music on The Voice of Firestone played for five years on NBC and another five on ABC to comparatively small audiences because the Firestone family was more concerned with attaching their name to a cultural show than they were with ratings.

Yet here was Serling in 1964, calling for a stronger hand from the FCC and pooh-poohing the idea that such intervention would constitute censorship — this just after the three-year reign of FCC chair and “culture czar” Newton Minow, who

gave networks authority and placed the power of programming in the hands of three network heads, who, for a long time, controlled everything coming into your living room. They eventually became the de facto producers of all prime-time programs by having creative control over writing, casting, and directing. (quoted by Russell Johnson, aka the “Professor,” Here on Gilligan’s Island)

In the famous “vast wasteland” speech before the National Association of Broadcasters in 1961, Minow told the television industry, “You must provide a wider range of choices, more diversity, more alternatives.”

“Yet,” according to University of Virginia professor Paul Cantor,

Minow’s speech resulted in centralizing power in the television industry and thus actually reducing the range of choices in programs.… [H]is words contained clear threats that if the television industry did not voluntarily do what he wanted, the FCC would make sure that it did. (Paul A. Cantor, “The Road to Cultural Serfdom: America’s First Television Czar” in Back on the Road to Serfdom: The Resurgence of Statism, edited by Thomas E. Woods, Jr.)

Rod Serling, the angry young man of Hollywood, clearly preferred the rule of the FCC to the rule of the American sponsors, and in 1964 — after three years under Newton Minow had radically changed the television landscape, and JFK-appointed FCC chair E. William Henry was still “fully committed to Minow’s agenda” (Thompson) — Serling all but advocated an even stronger hand from the federal government to limit commercial interruptions.

Is it possible that the sponsors were requiring ever more commercials in response to their dwindling power in the production end? After all, you don’t have to push Kraft-brand cheese slices as ardently when the anthology showing Rod Serling’s famous “Patterns” is called The Kraft Television Theater.

If that’s right, then Rod Serling is yet another example of the intervention spiral that Ludwig von Mises described: first you call for government intervention, then you fail to see that the intervention created the new problems you dislike, so you call for further intervention, and the cycle repeats.

So why wasn’t Serling afraid of implicit censorship from the FCC?

One unfortunate possibility is that Rod Serling was less vigilant about the FCC because Newton Minow’s agenda was better aligned with Serling’s own politics. Serling’s teleplays were antiwar well before antiwar sentiment took over a later generation. His stories also focused on questions of racial prejudice and sexual equality at a time when the sponsors considered the topics divisive and controversial. Recall that one of the edicts from “Advertisers Row” was that “at no time in a political drama must a speech or character be equated with an existing political party or current political problems.”

But in the early 1960s, the edict from Washington DC reversed the mandate.

Newton Minow was an appointee of the Kennedy administration. “His chief ‘qualification’ for the FCC job,” according to Paul Cantor, “was the fact that he was a personal friend of the president’s brother Robert Kennedy.”

Lacking any grasp of aesthetic criteria, Minow had to employ political criteria in his evaluation of television, and the industry responded accordingly.… [T]he changes in television content in the 1960s chiefly followed a political agenda — greater representation of minorities on shows, especially African-Americans; more dramas devoted to controversial political issues, displaying a deepened social conscience; in particular a number of shows dealing with the issue of civil rights, which not coincidentally was being promoted at the same time by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.… [T]elevision in the 1960s increasingly fell in line with the program of the Democratic Party. This is exactly what one might have predicted under the leadership of an activist FCC chairman appointed by a Democratic president. (Cantor)

If Rod Serling wanted to push the Democrats’ agenda, then pressure from the federal government for television networks to do exactly that may have felt less like oppression and more like freedom.

Serling may have welcomed the new era of the American culture czar. Minow certainly recognized Serling as a comrade in the crusade. In his speech to broadcasters, Minow had called television a “vast wasteland,” but he listed a handful of exceptions by name. Serling’s Twilight Zone was one of them.

The preachy tone I now hear in the show was a sign of the times. It felt familiar to me because I had grown up on 1960s television. I believe in tolerance and diversity largely because TV taught me to believe in tolerance and diversity. But over time, I came to believe that the tolerance of left-liberalism was a shallow tolerance, a tolerance only for certain forms of diversity — those that aren’t in conflict with the rest of the left-liberal agenda. That agenda was about more than cosmopolitan open-mindedness and acceptance of ethnic and cultural differences; it was about greater centralization of power, the need for coercive intervention, trust in certain elites, and a distrust of local values and local authority.

Serling may have seen a greater number of heroic, middle-class blacks and strong, smart women on television and believed that it was evidence that the medium was advancing. But did he also notice that the stories took fewer and fewer risks? Did he notice that the chorus of social consciousness could sing only one note?

He bridled against the sponsors’ mandate not to offend anyone and bemoaned the television writers’ practice of “pre-censoring,” by which he meant anticipating sponsor reaction and thereby avoiding any risks. And he was right that creativity requires risk-taking. In recent decades we’ve seen the cable-TV drama raised to the level of art precisely because commercial-free cable networks can afford to take chances that commercially supported broadcast networks just can’t.

But the strong arm of Kennedy liberalism, in the form of an activist FCC, drove risk-taking off the air and replaced it with homogeneity and blandness under the guidance of a fearful cartel of network heads who were willing to sing the administration’s preferred lyrics so that they could continue to sell soap. Rod Serling may have played a starring role in the golden age of television drama, but his agenda brought that age to an end.